Teaching Science through experiments

One of the biggest challenges facing science teachers in secondary schools is how to teach the relatively complex subjects of Physics and Chemistry (difficult enough in L1) to young learners with A1 or A2 levels of English.

With this in mind, Roser Nebot (with the support of Jane Kirsch) developed a practical science course for 2nd of ESO students, which aimed to take the emphasis away from teacher-led explanations and, instead, involve students in their own learning. In these classes, language remained an important tool in the transmission of scientific knowledge. However, it is used in conjunction with other, more visual, ways of conveying knowledge.

In this article we suggest five ways to help students learn scientific language and concepts in English.

Use realia and drawings to pre-teach the vocabulary for experiments

Before starting a practical activity with students, it is a good idea to elicit the materials they need by asking them to point them out or hold them up. Concept-check questions can also be asked to double-check understanding e.g. ‘Where we do we keep cold water?’ ‘In the fridge’. It is also useful to have a list of materials in front of students on a worksheet and encouraging them to draw pictures of the materials to help them remember.

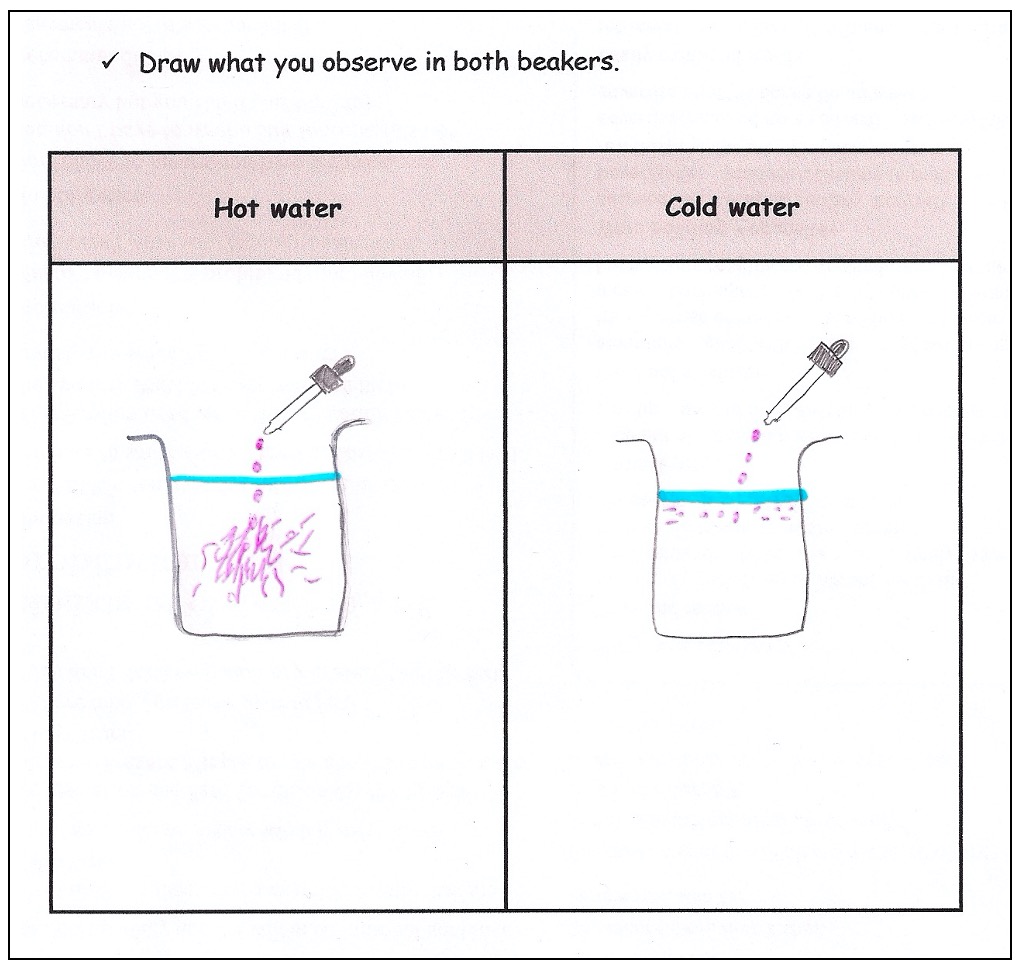

Ask students to draw what they see during experiments before getting them to put what they are observing into words.

In this experiment students put some drops of food colouring into a beaker of cold water and a beaker of hot water.

By getting students to draw (rather than write) what they see during the experiment, it doesn’t matter if students do not know the technical language to explain what is happening. Students with lower levels of English can still participate, while the teacher is free to monitor the activity rather than help out with unknown vocabulary.

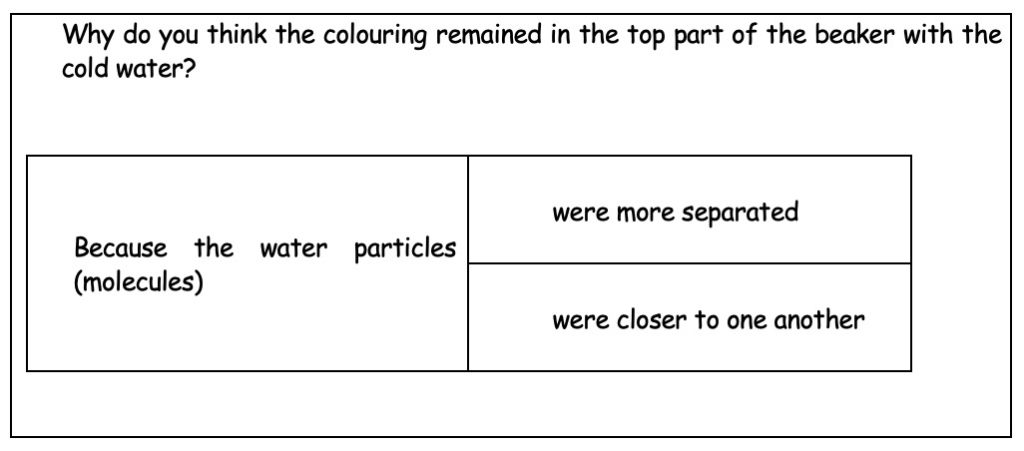

Use substitution tables to help students draw conclusions

After a practical experiment, students should be able to draw their own conclusions for why something happened, e.g. why the food colouring dispersed in the hot water and remained at the top of the cold water. However, explaining this in English could still be a challenge. By providing students with substitutions tables, teachers can check their understanding of the science without putting unrealistic linguistic demands on them.

Give students time to think of questions to ask in a plenary session at the end of a class.

The teaching team at IES Manuel Blancafort, where these lessons took place, noticed that students in CLIL science lessons tend to ask fewer questions (whether in English or in L1) than students in an L1 science class. As a result, we decided to create an activity where students work in groups and write the questions they want to ask at the end of an experiment. The advantage of creating these questions together is that the pressure to construct grammatically correct sentences on the spot is reduced. It also means that students become more comfortable asking questions about science in class and need less prompting in future lessons.

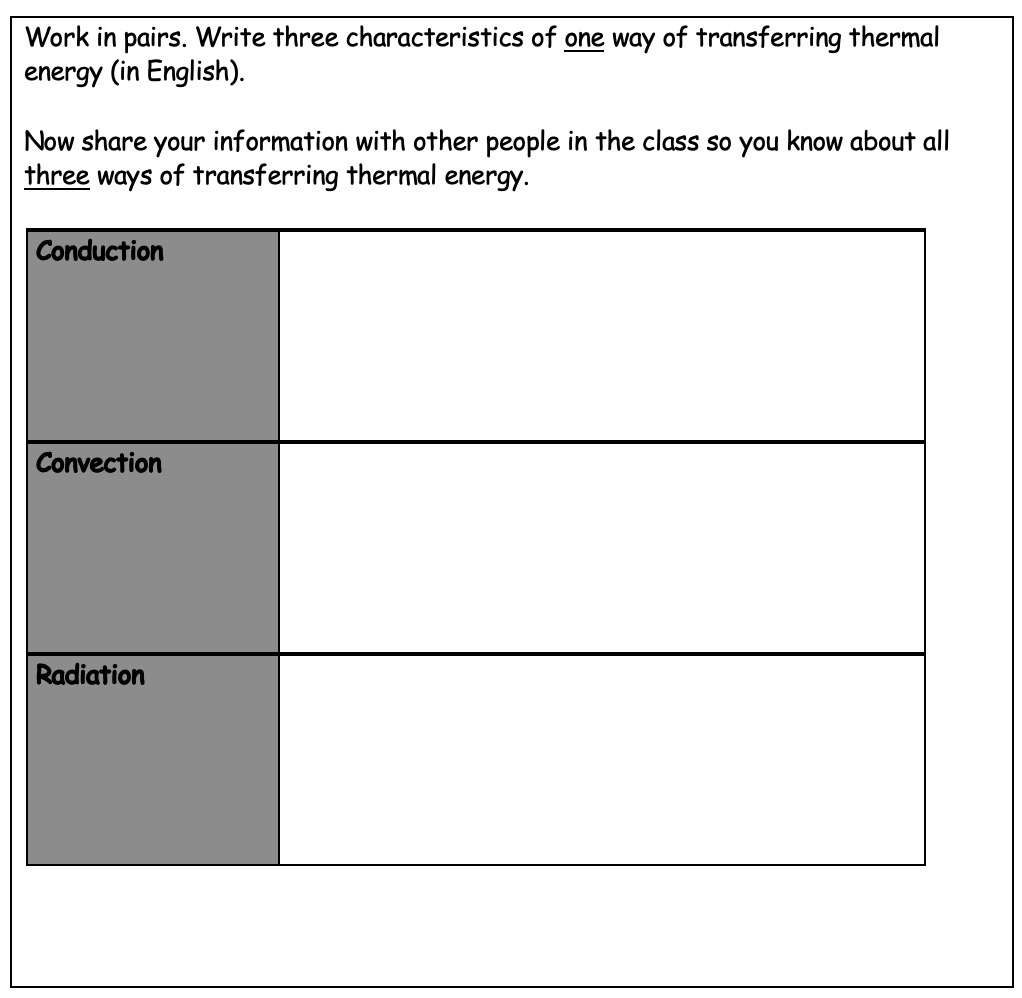

Use information gap activities to encourage students to speak to each other in English

Students almost always use L1 to communicate with each other in class, however we can design activities to get them speaking to each other in English. One way to do this is with an information gap activity. This task requires students to work in groups to write down the most important characteristics of convection, conduction or radiation based on information they find on the Internet. They then regroup and share their knowledge.

Jane Kirsch, 3 March, 2022

This article first appeared in Mac Mag (Macmillan).